IMCA Insights – February 2007

Our Favorite Chondrites, Part 2

by the IMCA Board of Directors

In Part 2 of "Our Favorite Chondrites" we'd like to present you with some more great samples that have a very special place in the hearts and in the collections of the IMCA Board Members. Enjoy!

Mark Bostick:

My favorite chondrite is the Wichita meteorite. This 2.3kg 1971 find is an "ordinary" chondrite with a common classification, H5. The meteorite has small regmaglypts (pits) (~3/4"), a trace of black crust and a pleasing shape. What makes the meteorite special to me is that it is from my hometown and is owned by the Kansas Meteorite Society, a local meteorite club I co-founded. When we first got the meteorite and helped it along to official status we put the meteorite on display and for the first time managed to get a good press response. I also appeared on television for the first time associated with meteorites. I wrote about the display and public reaction for the April 2004 Meteorite Times. In the "The Wichita Experience."

The 2.3kg main mass of H5 chondrite Wichita

Adam Hupé:

My favorite chondrite is from the Park Forest fall of March 26th 2003, specifically the Garza Stone. Although I do not collect falls, The Garza Stone represents the most historic chondrite in our collection. My second favorite is my first official cold find from Coyote Dry Lake although the memories surrounding the recovery and the people I met along the way are far more important to me.

When I hold the Garza Stone, it feels like touching history. I feel that it was the most publicized of the Park Forest event and maybe the most important, at least from a historical standpoint. Noe Garza was great to work with in its acquisition and acted as colossal media machine in its promotion. Noe thought of the Garza Stone as a gift from the heavens and showed it to everybody who was interested. He played an international field of perspective buyers perfectly and after months of negotiations, it was ours. This hard earned prize deserves a place in a museum not its current home, a safe deposit box.

Park Forest: The famous 2.3kg Garza Stone

An interesting note is that this battle-scarred meteorite never completed its journey to the Earth after becoming entangled in the house it heavily damaged. It is fascinating that this wrecking ball has never touched the ground or been out in the weather, although it did spend some time in the local pokey (jail) locked in an evidence bag labeled under charges of “N/A Act of God” and assigned a case number.

Christian Anger:

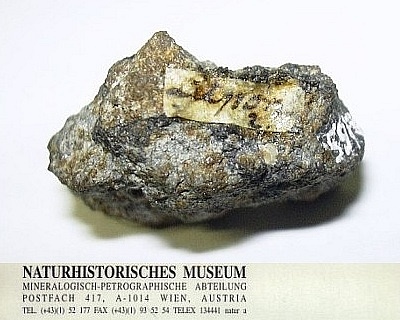

My favorite chondrite is the historical meteorite Luponnas which fell on September 7, 1753, at 13:00 hrs. It is a H3-5 chondrite breccia. After detonations, two stones were found, one of 9kg at Luponnas, France and the other of 5kg at Pont-de-Vesle (Jerome la Lande, Ann. Phys., 1803, 13, p.343).

Luponnas is the "birthday meteorite" of my son Michael who was born on Sept. 7, 1996. I got my collection piece in 2002 in a trade from Dr. Gero Kurat, NHM Vienna. Very little of this meteorite has been preserved. A total of just 211.44g is accounted for in collections.

A neat 5.752g fragment of Luponnas, Coll. Christian Anger

Ron Hartman:

LV4 is my favorite because it was the largest of the initial Lucerne Valley, CA meteorites found on Lucerne Dry Lake (LDL). The finds were significant because it began the great search for meteorites on dry lakes in California and Nevada. LDL remains the one dry lake where the greatest number of unrelated, overlapping strewn fields have been discovered to date. This has added much to the knowledge base about meteorite falls, their preservation and/or deterioration rates while still in situ, as well as the dynamics of dry lake surface change. The whole story must be told in context of the initial finds. (The complete story may be found on the LDL research site, from the link on the homepage at www.meteorite1.com.)

Circumstances of Discovery: In 1963 I became interested in investigating dry lakes for meteorites. A number of meteorites had been found on other nearby dry lakes, including Rosamond and Muroc (Rogers). It seemed worth the effort to investigate other nearby dry lakes. Not to say that one would expect meteorites to selectively fall on a dry lake bed, but rather, that once fallen, one could more easily be noticed as these regions are relatively free of rocks. One can search a large area rather quickly. A dry lake is also a basin. Once fallen, a meteorite is not going anywhere! It will remain until it either disintegrates or is possibly buried. The plan was to lay out a grid using grape stakes with painted tips, and search the entire region (a rather large one, at that). As luck would have it, the first specimen (LV1 in the literature) was located after only 2 hours, toward the end of the first day of searching on July 21, 1963. Its mass was only 15.8 g. In fact, the black fusion crust lay buried facing downward in a small blowout of small pebbles, just about 30 feet or so west of what is known as the old Barstow Road (Hyw. 247). The edge of the dry lake slowly merges into a hummocky grassy land, but this specimen definitely was in the SE corner of the lake itself. My attention was drawn to it by the broken section (the way it was broken!) which was facing upward. The very black fusion crust was, in fact, buried and not noticed until I picked it up! The specimen was weakly attracted to a magnet. A corner filed smoothly revealed metallic flakes.

The LV4 chondrite from Lucerne Valley, California

The second and third meteorites, LV2 and LV3, were found the next month, on our second trip, by Ronald Oriti, then lecturer at the Griffith Observatory whom I had invited to join in the search along with Robert Gale, Curator of Mineralogy at the Los Angeles County Museum. Soon thereafter, I found LV4 (37.4 g., one of the largest found to date) and LV5 (3.1 g.) within a few yards of one another. LV5 was in fact perched on the edge of a gully bordering the shoulder of the road, ready to tumble into fresh mud at the slightest whisper of wind. On the way home, it was discovered that the smaller was actually a small corner that had obviously only recently broken off the larger, and had washed down a slight grade toward the road.

Pierre-Marie Pele:

January 4th, 2004 at 5.47p.m., thousands of Spanish people observed a fireball crossing the sky before the sunset. The following day, «El Mundo» published a long article specifying that the bolide had traveled from north-west to the east and that many fragments had fallen everywhere, causing small fires. I was at home, having dinner, when the French TV News showed a movie of the fireball flying over the Spanish town of Leon. An amateur movie maker was filming the Three Kings procession in the streets of Leon and, suddenly, the meteor crossed the street, far behind several buildings and under the moon. According to the position of the moon at that time, Victor Ruiz, an amateur astronomer concluded that the meteorite moved from south-west to the north-east. On January 21st, a Spanish journalist, Abel Tarilonte, showed two chondrites of 21.76 and 42 grams to the Spanish National Museum of Science. He got them from a man who had discovered them before January 10th at Recueva de la Peña, near Villalbeto de la Peña. Between January and March 2004, about 15 meteorites were found by Spanish searchers, despite of the snow and bad weather.

A French man,

passionate about UFOs, had studied the video and contacted me. He had

made very difficult calculations to draw a nearly perfect trajectory and

points of impact. With his calculations, my team and I decided to go to

Spain. We wanted to search to the north of the area, behind mountains

which were across the strewn field, at the end of the theoretical

trajectory. As we feared it, snow covered the area. On the second day,

March 10, 2004, we went back to a place we had noticed from the car and

which seemed easier to hunt into. We walked during the entire day and

started to despair with again nothing to find. By chance or divine

intervention, while going back to our car, I discovered at the end of

the day the first meteorite that we had hoped so much for. And what a

find! It was on a muddy path and, if I had walked just a few meters

further, we would have missed it. Our discovery was accompanied by cries

of joy which may have been heard at a good distance. On the road back to

the hotel, we stopped by a supermarket to weigh the meteorite. It

weighed 1367.60 grams – that’s a lucky find. During the next three days

of hunting,

we walked during many hours, often in the sun, but also during one

complete day under rain and hail. We didn’t find anything more.

Villalbeto de la Peña: the 1367.6g mass in situ

We did three more trips to the Villalbeto area and discovered two additional meteorites, one of 39 grams in April 2004 and one of 145 grams in June 2006, in the southern part of the strewn field. In April 2004, the Museum of National History of Paris classified the meteorite and confirmed it was a L6 chondrite.

We intend to continue this series with our favorite achondrites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites in some of our future issues. Stay tuned, and thanks for your interest.

•

IMCA Home Page •

IMCA Code of Ethics •

IMCA Member List

•

Join IMCA •

IMCA Meteorite Info