IMCA Insights – March 2008

Our Favorite Stony-Iron Meteorites, Part 2

by the IMCA Board of Directors

This is the second part of Our Favorite Stony-Iron Meteorites, introducing you to some more fascinating samples that have a very special place in the hearts and in the collections of the IMCA Board Members. We had expected to see more pallasites here, but as you will see our Directors all opted for mesosiderite samples, this time - something that came to us as a surprise, but as a pleasant one. Enjoy!

Norbert Classen:

My favorite stony-iron meteorite is the Vaca Muerta mesosiderite, not just because of its curious name. This meteorite find from the Atacama desert, Chile, is most interesting for several reasons, and I love it because of its great compositional diversity. Vaca Muerta proves to be a true stony-iron, and not just due to the typical mesosideritic appearance of "normal VM". It also contains rather distinct lithologies such as most beautiful olivine clusters, and unusual eucrite-like nodules which are sometimes found separately in the Vaca Muerta strewnfield as so-called "eucrite pebbles".

A 21.6g Endcut of "Normal" Vaca Muerta, Coll. Norbert Classen

Normal Vaca Muerta shows a rather typical mesosiderite texture, and even the small stones of this rather ancient fall have been well preserved by the arid climate of the Atacama desert. The photo above shows a 21.6g polished endcut of normal Vaca Muerta with lots of nickel-iron and abundant pyroxene.

Vaca Muerta Olivine Cluster, 3g Slice, Coll. Norbert Classen

The photo above shows a partly translucent slice of an olivine cluster from Vaca Muerta, a most beautiful lithology that reminds a lot of a pallasite. However, free metal is rare in this lithology, and only the upper part of the sample shows a few spots of nickel-iron, marking the transition to the "normal VC" lithology.

Vaca Muerta Eucrite Pebble, 1.19g Slice, Coll. Norbert Classen

Last but not least, the photo above shows the arguably most fascinating lithology of the Vaca Muerta mesosiderite: a slice of one of the so-called "eucrite pebbles" which are compositionally and isotopically similar to the HED achondrites from Vesta. Scientists are still discussing a possible HED - mesosiderite connection, and - who knows - maybe one day we will know for sure if both meteorite classes share a common parent body, or at least a common impact history linking both groups together.

Andrzej Pilski:

There are so many

beautiful stony-irons that it is very hard to pick out a favorite.

However one meteorite is very special to me, because I could handle it

and learn its terrestrial history. When I was studying astronomy at the

Warsaw University, my professor of celestial mechanics, Dr. Maciej

Bielicki, told me his story about the Lowicz mesosiderite shower.

One day in March 1935, when he was a young astronomer at the

Astronomical Observatory of Warsaw University, he was asked by his boss,

Prof. Michal Kamienski to take a train to the town of Lowicz to

investigate reports of a meteorite fall. The Principal of the town's

School for Teachers had called Prof. Kamienski and told him that a

number of children in a nearby village had presented their teacher with

fragments of the meteorite which had apparently fallen a few days

earlier.

Soon Dr. Bielicki arrived at the village of Krepa, southwest of Lowicz.

Residents of the village told him that they had seen a brilliant light

in the night of 11/12th March, and heard loud thunderclaps and saw

stones falling from the sky. Next morning one witness of the fall found

a black stone "planted into the ground", as he said, and he was adamant

that it had not been there previously. The villagers managed to get the

stone out of the ground and realized it was relatively heavy. Believing

the stone may contain gold they decided to break it open. Instead of

gold they found bright metal which, at first, they took to be silver but

it soon dawned on them that the metal was, in fact, only iron. Still,

the villagers were curious enough about this strange rock as to want to

keep fragments as mementos.

Dr. Bielicki received three pieces of the broken stone - totaling about

2kg - and also two other meteorites, weighing 4kg and 1kg, which were

found in the fields near the village of Krepa. They were all brought

back to the Observatory and one fragment was later donated by Prof.

Kamienski to the President of Poland.

Then came World War II. In 1944 the Astronomical Observatory was

destroyed and burnt down together with all the meteorites. However after

the war Dr. Gadomski managed to find the large 4kg specimen among

debris. So I could keep in my hands a meteorite which was burnt twice:

during its fall through the atmosphere and then during World War II.

An Endcut of the Lowicz Mesosiderite, Olsztyn Planetarium Coll.

I suggested to cut a window into the meteorite to show its internal texture. My suggestion was accepted, and now the students of astronomy in Warsaw, Poland, can see the historical meteorite with its black crust and its brown and green interior. The resulting endcut was traded to the collection of the Olsztyn Planetarium and you can see this very specimen pictured above. It gets obvious from the image that Lowicz is a twin of the Estherville mesosiderite, at least texturally spoken.

Peter Marmet:

For several years I had

a 20.6 g piece of the Bondoc mesosiderite in my collection but

rather unnoticed. Recently I read a text by Al Mitterling, related to

the Bondoc recovery story in H. H. Niningers great book "Find a falling

Star". Immediately, I remembered my Bondoc piece and I read Niningers

story. Here's a short abstract of the text:

"This is the incredible story of the recovery of the Bondoc meteorite,

one of the largest, finest and most unusual stony meteorites yet

discovered only because of coincidental events and the persistance of

Dr. H. H. Nininger and Mr. John Lednicky, two ingenious Americans."

Nininger wrote: "We had been in the Philippines ten or twelve days in

1959 when I visited the office of the National Bureau of Mines, sure

that among thousands of samples that inevitably reach such an office,

there must be an occasional meteorite. 'Well, yes, once in a while such

a sample comes in; but who cares about meteorites?' I had the answer.

Might not the Bureau have such specimens on hand? Well, the director

thought, there should be one. It had come in not so long ago, a rounded,

rusty lump of what appeared to be nickel-iron, very badly weathered. The

official assured me the Bureau had no interest in the specimen and that

I was free to pursue the matter.

A pair of lawyers had contacted two Japanese geologists who desired an

iron mine, but when these two were escorted to inspect the prospect they

were disappointed: This was no iron outcrop, but only something that had

fallen from the heavens, and they turned away. To reach that remote

jungle location they had to spend several hours aboard a slow train,

then they waited for a bus that only runs when the weather and the roads

are not too bad. It normally takes one day to reach a costal village.

From there a small boat carried them to and into the mouth of a river.

Then they had tramped for ten hours through crocodile and

serpent-infested jungle only to find a lone metallic lump which they

judged to be of low-grade quality.

Ten years earlier a visitor from Manila to our museum on Highway 66 had

shown keen interest in meteorites. He was John A. Lednicky, a University

of Kansas graduate who had lived in Manila most of his life. He said

that if and when I needed assistance he would be glad to help. I decided

to write to John Lednicky to request the help he had offered. On

September 15, 1959, Lednicky wrote, that he must wait until after the

national elections because bandits were operating on the peninsula;

there had been considerable shooting. But after the election there

followed more rains, more typhoons; then an illness kept Lednicky in the

hospital for some time. On February 13, 1961 Lednicky wrote that he

visited the site and that he thinks it's not a meteorite.

But I was sure it was a meteorite and I wanted it more than ever. On

January 9, 1962 Lednicky reported that they had been able to load the

meteorite on a wooden sled, but that three carabaos (water buffalos) had

been unable to move it. With a larger bulldozer they finally managed to

move the meteorite to the mouth of a river. Now a raft was being built

on which the meteorite was - with great difficulties - finally towed to

Manila.

John Lednicky put three and a half years of effort and frustration into

the 'favor' he had offered in late 1958. Without him the Bondoc

meteorite never would have been recovered."

Well, now I look at my little Bondoc piece in a very different way and I

like to imagine what incredible story it would tell if it was able to

speak...

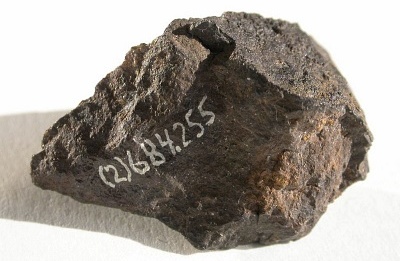

A 20.6g Endcut of the Bondoc Mesosiderite, Coll. Peter Marmet

BTW: The 20.6 g end piece of the Bondoc meteorite in my collection has a small number, painted with white ink (by H. H. Nininger?): (2)684.255. It comes from the ASU (Arizona State University). The base of the ASU is the Nininger collection, purchased in 1965...

More on our Favorite Meteorites in a future edition of IMCA Insights. Stay tuned, and thanks for your interest!

•

IMCA Home Page •

IMCA Code of Ethics •

IMCA Member List

•

Join IMCA •

IMCA Meteorite Info