IMCA Insights – March 2012

The Mysterious Hico Structure,

Hamilton-Erath Counties, Texas

by Paul V. Heinrich

Within Texas, credible

proposals have been made for the extraterrestrial impact origin of six

geological structures. Convincing cases have been made for three of

these structures, i.e. Marquez structure (Leon County), Odessa crater

(Ector County), and Sierra Madera (Pecos County), of being of impact

origin (Gibson 1990; Littlefield et al. 2007; Howard et al. 1972;

Wilshire et al. 1968; Wong 2001). The Bee Bluff structure in Zavala

County, Texas, is disputed (Sharpton and Nielsen 1988; Jurena et al.

2001). Another proposed Texas impact structure, the Wilbarger structure

in Wilbarger County, has been discredited by detailed field research

(Nelson 2006). The origin of the last of these structures, the Hico

structure, which lies in Hamilton-Erath County, remains an unresolved

mystery.

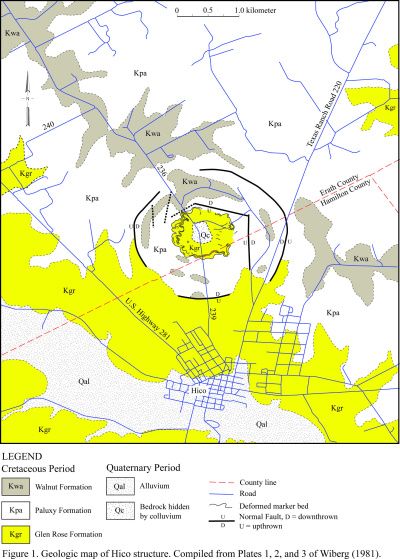

The Hico structure is a circular disturbance that is developed in Lower

Cretaceous strata, upper Glen Rose, Paluxy, and lower Walnut formations

about 3 km (1.8 miles) north of Hico, Texas and 32.085 degrees north

latitude and 98.0342 degrees west longitude. On aerial photographs, it

appears as a circular feature about 3 km (1.8 miles) in diameter (see

map). The arc segments comprising this anomaly consists of tree lines

and drainages associated with ring-like troughs, which encircle the

central uplift of the Hico structure. On Landsat imagery, the Hico

structure is at the center of a subtle 9-km (5.5-mile) in diameter

circular feature (Wiberg 1981, 1982; Milton 1987).

Map of the Hico

structure, Hamilton-Erath Counties, Texas

(Click the image to open a high-res map in a new window)

History

Mr. William J. McBride first discovered the Hico structure in 1953 while

mapping the geology of Hamilton County for Humble Oil and Refining

Company. In 1956, they drilled the center of this structure looking for

oil and gas. Unfortunately, well logs and other data acquired during the

drilling of this well and McBride’s original report were lost in a

warehouse fire (Wiberg 1981). If copies either of the report, well logs,

seismic sections, and other data were archived elsewhere and survived

the fire and could be located, they might provide invaluable data

concerning the origin of the Hico structure.

Later, Mr. Oscar Monnig, a Fort Worth meteorite collector and amateur

astronomer, pointed out this enigmatic structure to Dr. James R.

Underwood, who at the time was a professor for West Texas State

University, as a potential impact structure. Later, Dr. Underwood

suggested to Ms. L. Wiberg that the Hico structure would be a suitable

subject of study for a master’s thesis at Texas Christian University.

This research yielded Wiberg (1981, 1982) and Milton (1987).

Approximately twenty years after Wilson (1981, 1982), Heggy et al.

(2004) examined the Hico structure using ground penetrating radar and

analysis of SRTM Digital Elevation Model.

Local Geology

The bedrock, in which the Hico structure has developed, consists

predominately of nearly horizontal, Lower Cretaceous marls, limestone,

and sandstone, which dips about 3.5 m per km (18.5 ft per mile) towards

the southeast (Figure 1). The oldest strata exposed within the vicinity

of the Hico structure is 24 m (79 ft), which belongs to the upper Glen

Rose formation, of micritic and fossiliferous limestone alternating with

resistant beds of marls. Overlying the Glen Rose Formation is 15 to 20 m

(49 to 66 ft) of reddish brown, friable sandstone, which contain

hematite concretions, of the Paluxy Formation. Some 40 m (130 ft) of the

lower and middle Walnut Formation, which consists of calcareous clays

and thin-bedded limestones overlies the Paluxy Formation and outcrops in

the vicinity of the Hico structure. Both the Paluxy and Walnut

formations contained distinctive limestone and sandstone marker beds,

which were used to map the deformation of strata within the Hico

structure in detail (Wiberg 1981; Milton 1987).

Structure

As interpreted by Wiberg (1981, 1982) and Milton (1987), the Hico

structure consists of a circular feature, about 3 km (1.8 miles) in

diameter, consisting of a central uplift and a ring graben (Figure 1).

In addition, they noted that the Hico structure lies at the center of a

subtle 9-km (5.5-mile) in diameter circular feature of uncertain origin.

The central uplift of the Hico structure, as illustrated by Wiberg

(1981) and Milton (1987), consists of outer and medial zones of

circumferential folding surrounding the center of the structure, which

is hidden by colluvial deposits (Figure 1). The outer zone of folding

consists of open, undulating “pie-crust” folds, which are defined by the

marker beds recognized by Wiberg (1981). Towards the center of the

feature, these folds become tighter to form a medial zone of chevron

folds with axes radial to center of the Hico structure. These folds

consist of vertical or near-vertical beds of Glen Rose limestone.

Holocene and Quaternary colluvial deposits blanket the center of the

central uplift. As result, neither the age nor the structure of the

rocks comprising the center of this structure is known. Wiberg (1981)

and Milton (1987) suspects that the bedrock within the center consist of

Pennsylvanian age sandstones of the Twin Mountain Formation, which have

been uplifted by as much as 80 m (260 ft) (Wiberg 1981, 1982; Milton

1987).

Wiberg (1981, 1982) and Milton (1987) argue that a ring graben surrounds

the central uplift. They concluded that the outer boundary of this ring

graben is defined by a series of major faults, which are part of a ring

fault (Figure 1). The inner boundary of this graben consists of numerous

obscured faults, which have small displacement ranging from 8 to 18 m

(26 to 59 feet). Within the ring graben, erosional outliers of Walnut

Formation have been downfaulted into Paluxy and Glen Rose Formation.

Although largely obscured by alluvial and colluvial deposits,

circumferential folding also appears to be present within the ring

graben (Wiberg 1981, 1982; Milton 1987).

Wiberg (1981) reported observing a subtle 9-km (5.5-mile) in diameter

circular feature, within which the Hico structure lies at it center, in

Landsat imagery. She was unable to find a geological explanation for

this feature.

Later, Heggy et al. (2004) examined the Digital Elevation Model (DEM)

constructed from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data. They

found three previously unrecognized topographic rings, of which the

outermost one is 5 to 6 km (3 to 3.7 miles) in diameter. Ground

penetrating radar study of these rings indicated that these rings are

controlled by ring faults similar to those that form the outer boundary

on the ring graben.

They concluded that the outermost ring represents the true diameter of

the Hico structure. They make no mention of the 9-km (5.5-mile) in

diameter feature observed by Wiberg (1981).

Evidence of Shock Metamorphism

Wiberg (1981) collected samples of a marker bed composed of

calcite-cemented sandstone from outcrops of folded Paluxy Formation

exposed in the central uplift of the Hico structure. Powered samples of

this sandstone were analyzed using x-ray diffraction. No indication of

coesite, a high-pressure form of quartz created by extraterrestrial

impacts, was found in these samples. She also prepared samples of

sandstone and limestone from the folded strata from the central uplift.

She found a lack of any evidence of shock metamorphism in either the

sandstone or limestone samples (Wiberg 1981, 1982; Milton 1987).

Milton (1987) examined two borrow pits exposing friable limestone of the

Glen Rose Formation within the central uplift. In one borrow pit, she

found surfaces exhibiting convergent striations. Although the striations

are irregular due the friable nature of the limestone, they were

interpreted by Milton (1987) to be shatter cones.

Geophysical Surveys

Wiberg (1981) acquired gravity and magnetic data along transects across

the Hico structure. Analyses of this geophysical data revealed neither

gravity nor magnetic anomalies associated with its central uplift. She

did find weak Bouger gravity anomalies associated with the ring faults

associated with the ring graben (Wiberg 1981, 1982; Milton 1987).

Discussion

According to the Spray and Hines (2007), the principal criteria for

determining if a geological feature is an impact structure formed by the

hypervelocity impact of a meteorite or comet are (1.) presence of

shatter cones, (2.) presence of shocked quartz with multiple planar

deformation features within in situ minerals, (3.) presence of

high-pressure mineral polymorphs within in situ minerals, (4.)

morphometry of the structure, (5.) presence of an impact melt sheet

and/or dikes, and impact melt breccias, and the presence of impact

pseudotachylyte and breccias associated with radial and concentric fault

systems. So far in terms of these criteria, only the morphometry of the

Hico structure and report of shatter cones by Milton (1987) having been

found in a borrow pit appear to meet these criteria. Unfortunately,

Milton (1987) provides neither the detail descriptions nor photographs

needed to document the occurrence of shatter cones. As a result, the

existing published evidence is inadequate and insufficient to

demonstrate the existence of shatter cones associated with the Hico

structure.

The morphometry of the Hico structure is generally regarded as

insufficient proof of its impact origin. Unfortunately, circular

terrestrial structures, e.g., volcanoes, salt diapirs, glacigenic

features are generated by numerous other means, so the Hico structure’s

circular morphometry is not sufficient to prove impact structure status.

However, as discussed by Wiberg (1981, 1982) and Milton (1987), the

internal structure, which includes a ring graben and central uplift, of

the Hico structure is quite similar to known impact structures. This and

the lack of any plausible non-impact mechanisms for its origin, strongly

indicate, but do not prove, that it is an extraterrestrial impact

structure.

Conclusions

Although conclusive evidence for the extraterrestrial impact origin of

the Hico structure is still yet to be found, it appears that it is quite

likely an extraterrestrial impact structure. The search for definitive

evidence of shock metamorphism associated with the Hico structure is

still incomplete and more research needs to be done. First, the identity

of the bedrock underlying the center of this structure still needs to be

determined. Finding uplifted and deformed Pennsylvanian bedrock beneath

the colluvium covering the center of this structure will greatly

strengthen the case for the impact origin of this structure. In

addition, it is within the strata underlying the center of the Hico

structure where the best chance for finding shocked quartz exists.

Finally, the shattered cones reported by Milton (1978) need to verified

and better documented before they can be accepted as proof of the impact

origin of this structure.

In addition, another unanswered question is the significance of the 9 km

in diameter feature reported by Wiberg (1981). The existence and origin

of this circular feature was completely ignored by Heggy et al. (2004)’s

investigation of smaller circular features. Whether it is real, how it

formed, and what is its relation to the Hico structure remains an

unresolved mystery.

Paul V. Heinrich

Louisiana Geological Survey

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge, LA 70803

Acknowledgments

I thank Douglas Carlson, Assistant Professor of Research, Louisiana

Geological Survey for taking the time to review this article and his

advice on how to improve it.

References Cited:

Littlefield, D. L.,

P. T. Bauman, and A. Molineux. 2007. Analysis of formation of the Odessa

crater, International Journal of Impact Engineering, v. 34, pp.

1953–1961.

Gibson, J. W. 1990. Marquez Dome - an impact in Leon County, Texas.

Unpublished M.S. thesis, University of Houston, Houston, Texas, 65 p.

Heggy, E., F. F. Horz, A. Reid, S. A. Hall, and C. Chan. 2004. Potential

of radar imaging and sounding methods in mapping heavily eroded impact

craters: mapping the Hico Crater. 35th Lunar and Planetary Science

Conference, abstract no. 1462, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston,

Texas. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2004/pdf/1462.pdf, 224 KB

PDF file, last visited on September 28, 2007.

Howard, K. A. T. W. Offield, and H. G. Wilshire. 1972. Structure of

Sierra Madera, Texas, as a guide to central peaks of lunar craters.

Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 83, pp. 2795–2808.

Jurena D., B. M. French, and M. J. Gaffey. 2001. Planar Deformation

Feature Orientations and Distribution in Quartz Grains from the Carrizo

Sand Formation in South Texas: Relation to the Bee Bluff Structure.

Lunar and Planetary Science XXII abstract no. 1828. Lunar and Planetary

Institute, Houston, Texas.

Nelson, J. 2006. personal communication, November 2006, Illinois State

Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois.

Milton, L. W.. 1987. The Hico impact structure of north-central Texas.

in pp. 131-140, J. Pohl, ed., Research in Terrestrial Impact Structures.

University of Munchen, Munich, Federal Republic of Germany.

Sharpton, V. L., and D. C. Nielsen. 1988. Is the Bee Bluff structure in

South Texas an impact crater? In Lunar and Planetary Science XIX. Lunar

and Planetary Institute, Houston, Texas. pp. 1065-1066.

Spray, J., and J. Hines. 2007. Earth Impact Database.

http://www.unb.ca/passc/ImpactDatabase/index.html, last visited on

September 28, 2007.

Wiberg, L. 1981. The Hico Structure; a possible astrobleme in

north-central Texas, U.S.A. Unpublished M.S. thesis, Texas Christian

University: Fort Worth, Texas, 75 p.

Wiberg, L. 1982. The Hico Structure: a Possible Impact Structure in

North-Central Texas, USA. 13th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference,

Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, Texas, p. 863-864.

Wilshire, H. G., and K. A. Howard. 1968. Structural patterns in central

uplifts of cryptoexplosion structures as typified by Sierra Madera.

Science, v. 162, p. 258-261.

Wong, W. A. 2001. Reconstruction of the subsurface structure of the

Marquez impact crater in Leon County, Texas, USA, based on well-log and

gravity data. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, v. 36, no. 11,

p.1443-1455.

This

article is a re-print from the Houston Gem and Mineral Society

Bulletin,

and it is published with permission.

•

IMCA Home Page •

IMCA Code of Ethics •

IMCA Member List

•

Join IMCA •

IMCA Meteorite Info